Death, a phenomenon long unexplored, and the fear of it are drawing interest from medicine and science.

Livres:

Mourir, ce que l’on sait, ce que l’on peut faire, comment s’y préparer, (Dying, what we know, what we can do and how to prepare for it), Gian Domenico Borasio, PPUR, 2014

La Mort (Death), Alexandrine Schniewind, PUF, 2016

La mort, une inconnue à apprivoiser. Des étudiants en médecine engagent une réflexion“ (Death, a stranger worth knowing. An analysis by medical students), Marc-Antoine Bornet, Arnaud Bakaric, Sophie Masmejan and Sophie Kasser, Editions Favre, 2013

Vidéos:

It’s not about dying, TEDxCHUV Talk by Gian Domenico Borasio, 2014

Voilà comment je veux mourir, segment from

the show “Temps

présent” aired on

Thursday, 13 October

2016, rts.ch

Online:

penserlamort.ch, website of the Society of Thanatological Studies

Two of the most widely read popular science collections in Switzerland—Que sais-je? and Le savoir suisse—have recently published books on death. Just a coincidence? Ordinary people have always been curious about it, but now science also wants to understand death better. Let’s face it, death has long been taboo and has not been given much attention. “We have gained extensive, precise knowledge about the beginning of life, but death has remained relatively unexplored,” says Gian Domenico Borasio, chief of the Palliative Care Service at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), in his book Mourir.

This growing interest comes at a time when the lines defining the “end of life” are being blurred. “The concept of brain death has brought new possibilities—primarily organ transplants—and changed the way we see death,” says Marc-Antoine Berthod, president of the Society of Thanatological Studies in French-speaking Switzerland.

“People have long been fascinated with what happens after death,” says Alexandrine Schniewind, professor of philosophy at the University of Lausanne (UNIL) and author of the book La Mort. “And for centuries the Church has taken an ambiguous stance on the after-life.

The idea is both scary, when it comes to thinking about purgatory and hell, and comforting, with promises of heaven for those with the faith.” Religion’s weaker control over society and today’s longer life expectancy have displaced the issue. Now, both believers and non-believers express their hopes of having a “good death”.

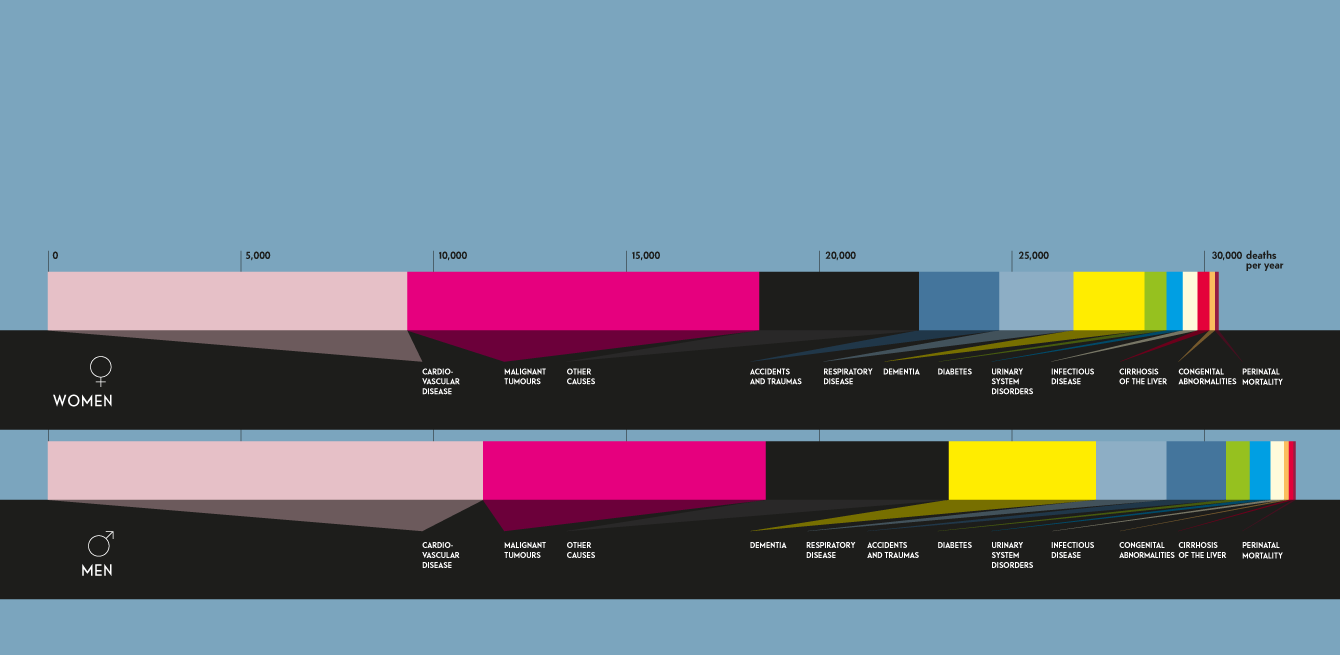

The Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) estimates that the percentage of people age 65 and over in Switzerland will rise from 17% in 2010 to 28% by 2060.

Palliative medicine is addressing those wishes by offering care that does not try to extend life but improve its quality. Palliative care has grown with the ageing population.

That means the need for palliative care will increase accordingly. To meet this demographic challenge, a chair in geriatric palliative care—the first in the world—was set up this year in Lausanne.

“We’ve never been so distant from the dying,” Schniewind notes. “Until the beginning of the last century, people ended their lives at home, surrounded by their family.” Now, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. In 2009, 41% of Swiss people died in hospital, versus 40% in homes for the elderly and 20% elsewhere, according to the SFSO. “We’ve delegated end-of-life support to health care providers, without realising that every one of us is (or will be) affected by this issue.”

These days more than ever, the topic of death is very much alive. And this affects medical professionals, as they are not always adequately prepared to face it.

1/ Supporting future doctors:

An organisation that keeps them informed

Death became more clearly

de ned from a scientific point

of view in the 1960s, mainly due

to progress in organ transplantation.

In Switzerland, the Swiss Academy

of Medical Sciences set out its initial

directives in 1969, which have

since been revised several times.

Today, the document entitled

“Directives for the definition and

diagnosis of death for organ

transplantation” stipulates that

an individual is dead after sustaining

“irreversible cessation of the entire

function of the brain, including

the brain stem”. But this definition

could be adjusted as practices

evolve .

Having noted the lack of information about death in the medical community, a group of UNIL students founded the organisation Doctors and Death five years ago. What got them thinking was the “cold, mechanical” aspect of dissection labs. “Most medical students who come to the anatomy room face death for the first time,” says Loïc Payrard, vice-president of the Lausanne branch.

“Medical school is very competitive, and showing emotion when faced with death is often perceived as a weakness. That creates a serious ambivalence. On one side, we want practitioners to be empathetic, while on the other they are forced to be cold.” The Doctors and Death initiative, which began in the Canton of Vaud but has since spread throughout the country, wants to take away some of the guilt experienced by students who feel emotion when dealing with death. The organisation offers them a space to talk about it—for example through a monitoring unit run by experienced professors—and get information.

By extension, the organisation also aims to develop better ways for doctors and patients to communicate with each other about death. “I still know too many health care providers who are incapable of talking about the subject, probably because this forces them to deal with their own powerlessness.” However “the fact that we cannot avoid death does not invalidate the importance of what we do, part of which means being honest with our patients. In any case, they have access to loads of information with the development of new technology.”

PALLIATIVE CARE Itinerary exhibition

2/ The point of palliative care:

Dying in peace while in hospital

Future doctors are more aware about the issues involved in death, and that’s a step in the right direction. In their third year of undergraduate studies, medical students from the Faculty of Biology and Medicine (FBM) are now required to spend two days as observers at a palliative care unit. For doctors’ assistants, CHUV offers special training on death and palliative medicine depending on the needs of the different departments.

Gian Domenico Borasio is the only full professor of palliative medicine in Switzerland. For several years, he has been working with his team to bring about a change in attitude about the last phase of patients’ lives. Every year the hospital organises a half-day event focusing on the issue of medical futility. “Many institutions completely deny that any problem exists,” Borasio says. “There’s still a tradition of trying to extend a patient’s life at all costs.”

The aim of palliative care is not to extend life but to improve the quality of life. “It’s crucial that we shift towards a culture of listening to patients to understand how they want to live the last moments of their life,” says Emmanuel Tamchès, head of the mobile palliative care team at CHUV. “Health care staff must communicate with compassion and respect the different values of patients.”

Historically, palliative care is primarily given to cancer patients but is increasingly considered an option in other end-of-life situations. To address the needs of its departments, CHUV has developed a programme that identifies beds with patients in need of palliative care. “For now the project has ten beds. Patients can stay in their original unit but come under the medical responsibility of a team specialised in palliative care,” Tamchès says.

The ageing population has also brought new challenges. “This means that we have to plan for situations involving elderly people who will die of complications linked directly to dementia,” says Eve Rubli Truchard. The world’s first chair in geriatric palliative medicine was set up on 1 May 2016. It is led jointly by the geriatrics department and Ralf Jox, a neurologist, ethicist and palliative care expert. “We often intervene when it’s too late, at a stage when patients can no longer express how they want to experience this final phase. Communication with loved ones is vital in these cases. We have to guide them in their decisions by suggesting consistent solutions.”

3/ Donating a dead heart:

An ambitious ethical challenge

Death in the hospital environment is intimately linked with the sensitive issue of organ donations. And that raises a fundamental point. What are the conditions that determine when a patient has actually died? Death has always been defined as a complete cessation of vital functions. But a new concept emerged in the 1970s: brain death. Death was now diagnosed based on the interruption of brain functions, but the heart kept beating. “Most transplants involve organs from donors who are brain dead,” says Manuel Pascual, chief of service at the transplantation centre at CHUV.

But due to the lack of donors, in both Switzerland and abroad, practices are changing. The university hospitals in Zurich, Geneva and Lausanne now perform “dead heart” transplants. “This means that donors have suffered extensive, irreversible damage to the brain but do not meet all the criteria for brain death,” Dr Pascual explains. “We talk to family members and, if they agree, we decide to unplug the machines, and cardiac arrest ensues.”

This new paradigm could increase the number of dead donors identified in intensive care units by about 20%. But that brings a whole new set of challenges. So hospitals have implemented ethical safeguards. “The decision to switch off the machines must be completely independent from the possibility of organ donation and transplantation. Neither the family or health care staff should feel any pressure whatsoever.” To make sure that these two procedures remain clearly separate, “we’ve held dozens of internal information meetings,” says Philippe Eckert, chief of the Service of Adult Intensive Medicine at CHUV. At the Lausanne University Hospital, approximately 200 patients die every year because their treatment is withdrawn or withheld, thus causing their death. But Dr Eckert estimates that “annually only about 10 of these cases will lead to a dead heart transplant.”

Dead heart transplants also involve a logistical challenge. This method gives surgeons less than one hour to remove the organ. As blood flow has stopped, the entire surgical team has to act fast and be perfectly coordinated. Eckert agrees, “Guaranteeing the quality of organs while respecting the dead and their loved ones turns into a race against the clock.” The complexity of the process is in fact “one of the reasons why we have long refused to perform dead heart transplants,” Pascual says.

4/ Near death experience:

A phenomenon at the heart of neuroscience

Advances in neuroscience have brought new insight into near-death experiences (NDEs). These phenomena have been described since ancient times and have continued to feed our imagination, often associated with mysticism or charlatanism.

NDEs were thrust into the contemporary spotlight in 1975, when the physician and psychiatrist Raymond Moody published his famous report Life After Life. His book draws on a collection of cases to identify the common elements most often described by people who have been through an NDE, including a white light at the end of a tunnel, encountering deceased loved ones, sensation of floating above their own body, and contact with a transcendental being.

In 1960, 19.8% of men died after the age of 80. Today, 51.2% of men live to that age. These numbers confirm a strong demographic trend—the Swiss are living longer.

Switzerland has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, just behind Iceland for men (85 years) and after

Japan for women (80.7 years).

These experiences have been taken seriously by scientists ever since. In 2001, the first prospective study on the subject was led in the Netherlands by the cardiologist Pim van Lommel. It showed that 12% of patients resuscitated after a cardiac arrest had an NDE. This takes us from the certainty that the brain stops a few seconds after the heart to a new hypothesis of death in stages.

Published in 2014, the AWARE study—the biggest ever on the subject, conducted over four years involving more than 2,000 patients in hospitals in the United Kingdom, United States and Austria—showed that NDEs occur within about three minutes. It also found that nearly four out of ten cardiac arrest survivors indicated a sensation of consciousness but were unable to recall any specific memories. However, of that 39%, only 9% described experiences that could be defined as NDEs.

Other recent neuroscience studies are also seeking answers. One of these is a piece of research by a team from the University of Michigan. The tests run on rats showed that brain activity shot up for 30 seconds after the heart stopped beating, especially in the areas associated with consciousness and vision. Dr George Mashour, one of the co-authors of the study, believes that the visions described by people who have had an NDE could be explained by the communication gone haywire between the different parts of the brain. However, nothing indicates that the findings would be similar in humans.

Although the specific causes and limits of NDEs remain highly debated, “one thing is sure,” says Gian Domenico Borasio in his book Mourir: those who’ve come near to death say that they fear it less and are more at peace about facing it. Their accounts should be taken in a positive light. /

TRUE Even though the objective of palliative medicine is not to prolong life but to improve its quality, studies have clearly shown that administering palliative care early can also significantly extend the life of patients.

FALSE In some cantons, such as Vaud and Geneva, assisted suicide is authorised in the hospital if, for example, the patient cannot return to his or her home. However, health care personnel are not authorised to help patients die. Patients must use an external association, such as EXIT.

TRUE In Switzerland, 80% of people die in hospital or specialised homes. If someone wants to die at home, they can, in theory, but as long as their loved ones are prepared and able to handle most of the care needed.

FALSE Organ donation is not allowed unless the donor has given prior consent. If there is no document stating the deceased person’s refusal or consent, his or her organs can be donated upon consent of the family.

FALSE When organs are deprived of oxygen within the body, they cannot be donated after 30 to 60 minutes have passed. Ischemia tolerance—the time an organ can survive without oxygen—varies from one organ to another.