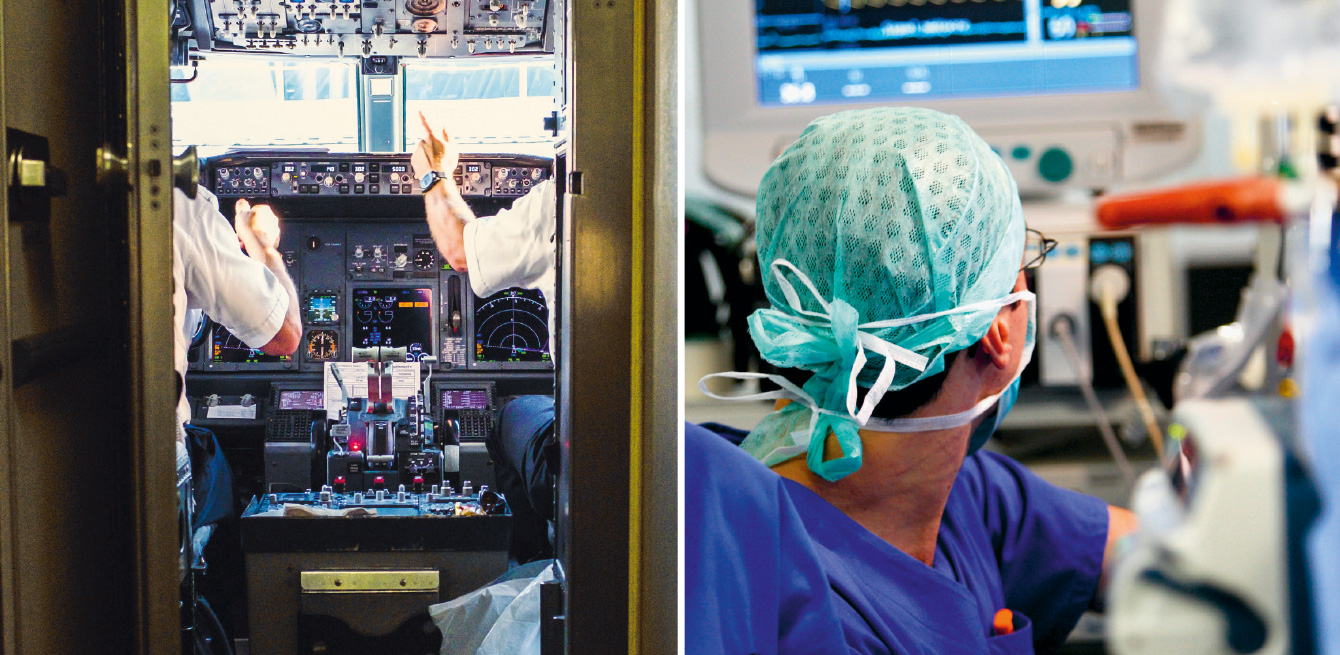

Before a flight, the flight crew methodically checks a set of flight parameters. This structured communication based on checklists is now inspiring hospitals.

Important details can get lost in the constant, meandering flow of instructions between teams. Crucial points to check before any surgical procedure get omitted, and these little lapses can have serious consequences for a hospital. Around the world, it is agreed that “60% of medical errors are caused by poor communication,” says Nahid Yeganeh-Rad, healthcare quality and safety coordinator of the Medical and Healthcare division at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV).

Information accuracy is also a question of survival in aviation. In the 1950s, the industry adopted techniques to optimise the transmission of information between and within flight and ground crews. “Checklists exist for each operation before and during the flight,” says Timothy Kriegers, founder and president of the organisation Pilotesuisse and Airbus airline pilot. “They are adjusted every time there’s an important incident or accident, such as the collision between two Boeing 747s in Tenerife in 1977 and the water landing of an A320 on the Hudson in 2009.” Special tools have been designed to enable crew members to make effective decisions should an unexpected event occur. “SPORDEC (Situation Catch, Preliminary Action, Options, Rating, Decision, Execution, Controlling) guidelines aim to ensure that crew members take an unbiased, objective perspective of a situation,” the pilot explains. “They reduce the stress of an individual who has to manage a crisis and prevents that person from limiting themselves to a narrow viewpoint.”

These methods have gradually been rolled out to other professional environments where potentially high-risk decisions are made.

Developed in the United States, the TeamSTEPPS framework borrows some procedures from aviation and transposes them into a hospital context.

The processes meet several needs: structure (definition of roles), communication (diverse tools, see inset), leadership (briefing, dialogue, debriefing), situation monitoring and mutual support. “In 2017, CHUV’s senior management decided to implement a protocol to make sure certain information passed on orally during critical processes does not get lost,” Ms Yeganeh-Rad says. The hospital has selected five tools from the TeamSTEPPS system and will integrate them into its different services. TeamSTEPPS will be applied over three years, from 2019 to 2021, starting with intensive care and emergency services, followed by intermediate care and finally long-term care. So far, 1,100 medical and nursing staff members have been trained, but 4,000 employees will eventually be using these tools. A two-hour e-learning course teaches them the basics, and long-term support will also be provided in the form of simulation sessions and coaching.

Among the five tools selected by CHUV is the I-PASS protocol, which will be used by the Internal medicine service to optimise verbal handoffs when changing shifts. The five letters in I-PASS stand for actions to be taken or information to be passed on about the patient’s condition.

“Even though it’s not a miracle solution, this kind of process clearly highlights the essential points to watch,” says David Gachoud, associate physician with the Department of medicine.

Compliance with protocol shows the instability of a case. That way, the new team will know that it has to pay close attention to certain indicators. “Before, we would already point out any measures to be taken, but now we proceed in a more structured manner, specifying who does what. Anticipating risks also means that each situation is discussed more systematically.” The handoff takes 30 minutes for the 16 patient beds in the intermediate care unit at the CHUV’s Internal medicine service, about as long as it used to take before the structured handoff procedure was implemented.

Another tool inherited from aviation is the surgical safety checklist to make sure that all necessary measures have been performed correctly before, during and after a procedure. This rigorous process aims to avoid “never events”, adverse and completely preventable situations that can have serious consequences, such as operating on the wrong leg. “Our checklist is based on the one developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) several years ago,” says Antoine Garnier, senior physician at CHUV.

In 2009, American surgeon Atul Gawande published The Checklist Manifesto to promote this form of discipline. In 2013, the Swiss Patient Safety Foundation conducted an in-depth study on applying checklists at Swiss hospitals. The CHUV’s Children’s Hospital was one of ten establishments in Switzerland to participate in the test project. Since then, the practice has been rolled out to all of the hospital’s surgical services.

“Most importantly, it’s a time when an entire team can come together to discuss patient safety,” Dr Garnier says. “When every member of a team participates attentively, we can share risk detection and be more efficient and therefore avoid critical incidents.”

In the same way, on airliners, every point is checked systematically: from the pilots who check that doors are closed to the purser and flight attendants who check that a megaphone is on board. Extremely precise and internationally recognised terms have been defined to ensure smooth communication between the ground crew and the cockpit. “It’s said that 80% of communication is non-verbal,” Mr Kriegers says. “With no visual contact with the control tower or even the co-pilot, because they’re looking straight ahead, every word uttered becomes extremely important.”

At CHUV, structured, effective communication using the TeamSTEPPS method reassures staff members. “They say they can leave work with greater peace of mind,” Ms Yeganeh-Rad says. In coordinating the implementation of the TeamSTEPPS system, she has even noted a “rare enthusiasm” with some services, which have decided to adopt it ahead of the scheduled date.

That means that it is not just about replacing one routine with another. The surgical safety checklist, used for several years now, is being overhauled. “We have to make sure these practices keep their meaning,” Dr Garnier says. “It can’t just become a to-do list that is checked off robotically, but a time for dialogue.”

Illness severity:

rate the patient’s acuity into the categories “ stable”, “watcher” or “unstable”.

/

Patient summary:

highlight important factors, active problems.

/

Action list:

determine concrete to-do tasks and who is responsible for them.

/

Situation awareness:

anticipate risks and set directions for what to do if a problem arises.

/

Synthesis by receiver:

reformulate actions to implement.

SBAR:

Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation, decision-making tool.

/

Handoff acknowledgement:

to make sure the message is understood, the person giving information has the receiver repeat what he or she has heard, and the giver confirms.

/

Two-challenge rule:

if one team member feels there has been a safety breach in patient care, that person must voice the concern at least two times.

In his book The Checklist Manifesto, surgeon Atul Gawande describes the increasing complexity of day-to-day tasks, which have become inevitable sources of errors. So the author set out to meet airline pilots and came back with a solution. Healthcare professionals need checklists, written handbooks to guide them, point by point, through the key steps of any procedure.