Philosophical counselling, a recent development in Switzerland, looks at life’s existential questions and gives health care providers insight into dealing with patients.

It was the sudden death of her husband that pushed Françoise* to seek the help of a philosopher in 2013. At the time, she was full of questions, about death, loss, the meaning of life. For one hour a month over the course of a year, she met with the philosophical counsellor Jean-Eudes Arnoux, based in Lausanne. “I wasn’t looking for a solution,” says Françoise, “but for a way to go on living”.

Alice*, suffering from depression after a stressful redundancy,went to consult the philosopher Georges Savoy in Fribourg, “for his listening skills and his way of expressing certain things. Going to see a professional helped me gain some perspective in a trying situation.”

Although the process seems akin to seeing a psychologist, it’s not quite the same, as Jean-Eudes Arnoux, a pioneer in philosophical counselling with an office practice in French-speaking Switzerland, points out: “Psychotherapy approaches problems in terms of illness, i.e., a medical point of view, while philosophy looks at them in terms of living conditions, i.e., from an existential point of view.”

While psychotherapy generally uses drugs and science, philosophical counselling is based on a broader reflection: humanity’s place in history, on the planet, the role of feelings and emotions in people’s lives, etc. The most common issues dealt with are happiness, death, love, romantic relationships and work. “I see both young people who are having trouble adapting and heads of companies,” says Georges Savoy.

Each philosopher has his or her way of doing things, resulting from their own background, convictions and intellectual preferences, and adapts it to his client. “I don’t have just one method, but for me, psychoanalysis is important,” says Georges Savoy. “I help people develop their own ideas, desires and fears. To become themselves, actually. That’s the Socratic tradition.”

Emmanuelle Métrailler, a philosopher in Valais, works with Platonism. She helps her patients reconnect with all the power of their soul and the dimensions of their personality to “regain harmony and integrity between what they say and what they do.” This approach is close to that of Jean-Eudes Arnoux, who focuses his thinking on the relationship with truth. “I don’t know if philosophical counselling makes people happy, but it makes them more lucid. The clearer our minds, the more capable we are of accepting ourselves and living an authentic life.” ⁄

WHY INVOLVE PHILOSOPHERS IN MEDICINE?

Friedrich Stiefel, head of the Liaison Psychiatry Service at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), has been working with the philosopher Hubert Wykretowicz for two years. Their aim is to assess acquired knowledge that seems natural and logical and to question it. They look at ways of understanding disease, the patient, patient relations and practices. “A sick person is not just a biological body that envelops a mind. That individual is a gure that changes with time and point of view,” the psychiatrist says. The purpose of his work with the philosopher is not to nd a speci c treatment. If there’s any “treatment” at all, it should be for the health care providers, to raise their awareness and expand their perspective. “If we take the example of a patient su ering from Parkinson’s disease, that person’s history is not simply the accumulation of neurological symptoms and the potential mental distress that goes with it,” says Friedrich Stiefel. “The patient also feels his or her body in its existential dimension: the body I have, the body I am, the body that connects me with others, the body that looks, the body that is looked at, etc. There is also the slowdown of motor functions and impairment caused by muscle sti ness that change their relationship with time and space. These changes in perception are not discussed in medical training. Studying the dimension of experience – at the heart of what patients are going through day to day – would help medical professionals develop their knowledge and understanding of the sick person.” Other elds of study that are not typically associated with medicine, such as linguistics, anthropology and sociology, are joining this initiative to question and understand human beings in this changing world, including patients and the people who provide their care.

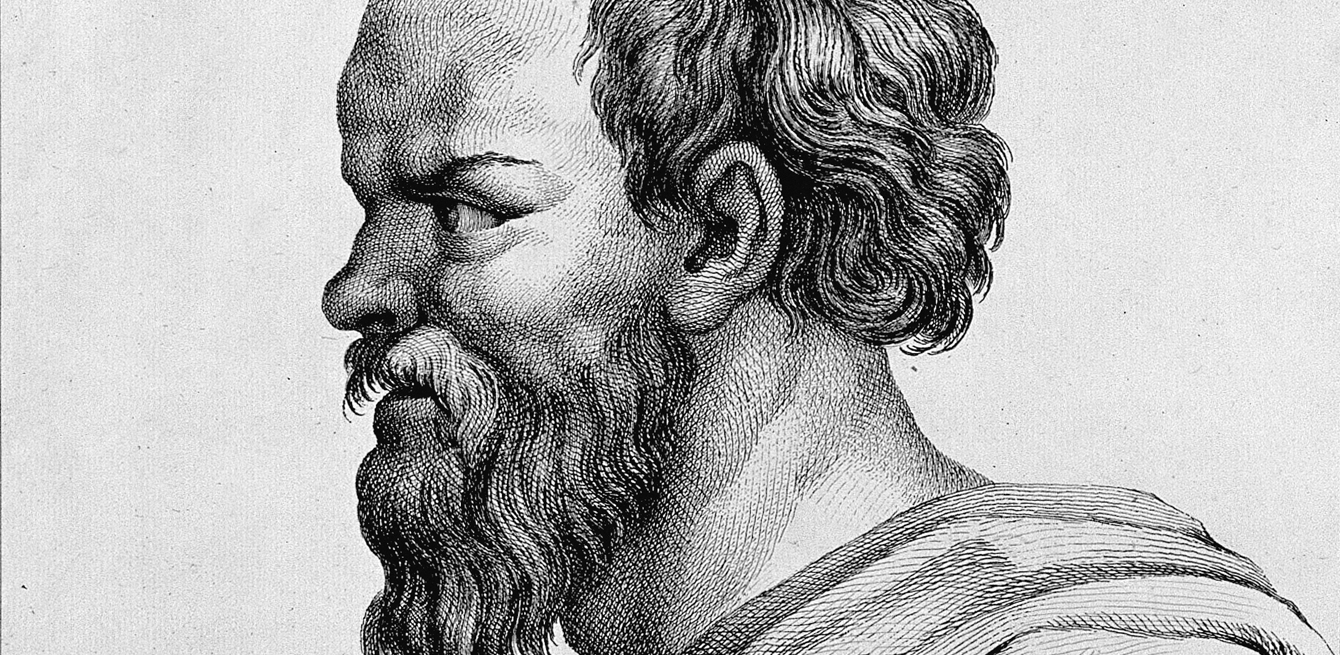

Considered to be the founder of philosophy, this Greek thinker (4th century BC) practised maieutics, i.e., a term which refers to using rational interrogation and reasoning to reach a truth.

Developing since the 1980s, the practice has been in existence for about half a dozen years in Switzerland and, for the time being, is not regulated. Counselling sessions are not covered by the health care system.

In ancient times, humans were defined by their nature, a rational being made of flesh. The first philosophers, such as Plato and Seneca, were masters of both thought and living. Philosophy is meant to be a form of counselling – from the Latin consilium meaning “consultation”, “advice” – to help people live in harmony with their body and soul. In the 20th century, humans were primarily defined by their condition and emotions, by phenomenology, a philosophical school of thought that aims to explore the transcendental structures of consciousness. The function of philosophy was therefore reduced to thinking about existence. Medicine was considered the only legitimate science for studying the disorders of the body.