Serious tropical diseases are neglected due to their lack of commercial potential. This French-born physician says it’s time for an alternative model.

www.dndi.org

Jul 03, 2015

After more than a decade of effort and achievements, Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) hands over malaria programme to Medecine Malaria Venture (MMV)

The 2014 World Malaria Report stated that in the 97 countries and territories with ongoing malaria transmission, 43,000 fewer people died in 2013 from malaria than in 2012. This is encouraging news. However, 584,000 people died of malaria in 2013; so, much still remains to be done if the lives of these vulnerable patients are to be saved.

The DNDi role

As part of these efforts to fight malaria, the Fixed-Dose Artesunate Combination Therapies (FACT) consortium was established in 2002 by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Working Group of the MSF Access Campaign with WHO-TDR, and subsequently transferred to DNDi when it was established in 2003. FACT aimed to develop two fixed-dose artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) associating artesunate (AS) with amodiaquine (AS) or mefloquine (MQ), two of the treatments recommended by the WHO in response to increasing chloroquine resistance, but that were not available in field-adapted fixed-dose formulations. These were to be easy-to-use formulations, suitable for both adults and children, affordable, stable in tropical conditions, and available on an unrestricted license as public goods. FACT pioneered innovative approaches to drug development, working with the pharmaceutical industry, start-ups, academia, NGOs, national control programmes, and other partners through its flexible, ‘virtual’ model.

These two projects demonstrate the ability of new, innovative partnerships between public and private actors, with a strong commitment from endemic countries to develop, deliver, and disseminate new high quality, affordable treatments within a short time frame. The dedication and commitment of the members of the FACT consortium, chaired throughout by Professor Nick White, has been invaluable, and its success is notably due to the enormous contribution of Jean-René Kiechel, PhD, who has led the DNDi malaria portfolio since its inception.

‘ASAQ and ASMQ fixed-dose antimalarials were among the first challenges in developing new treatments that we took on at the outset of DNDi and these two projects have now reached fruition’, said Dr Bernard Pécoul, Executive Director of DNDi. ‘We have learned and gained incredible experience in terms of the development process, the innovative partnerships formed, and pathways forged, as well as the rapid implementation of the treatments to reach patients. These projects have proved how essential a nimble partnership model is to success, and how crucial the engagement and dedication of numerous public and private partners, and individuals, are to reaching a common goal.’

http://www.dndi.org/media-centre/news/2175-dndi-mmv-handover-statement.html

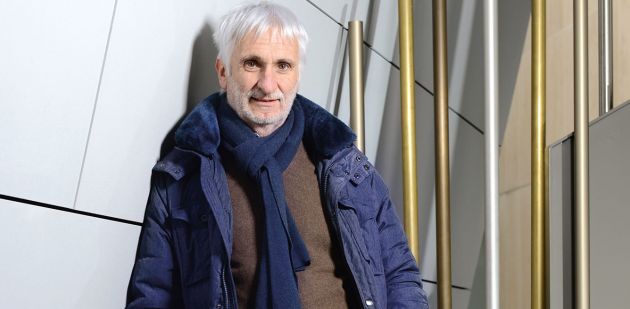

Malaria, African sleeping sickness or leishmaniasis. These extremely common diseases in developing countries have largely been ignored by the pharmaceutical industry. The physician Bernard Pécoul, director of the Geneva-based non-governmental organisation Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), met with In Vivo for an in-depth interview. He describes the devastation caused by a business model incapable of meeting the needs of the least fortunate.

IN VIVO Today, there is still no adequate treatment for Chagas disease, which kills nearly 13,000 people every year. Why?

BP This tropical disease caused by a parasite is one of the so-called “neglected” diseases. Pharmaceutical companies are not interested because it only affects poor populations in Central and South America and therefore lacks commercial appeal. That is also why many widespread diseases in Africa and Asia are not part of any research and development programmes, simply because they are outside the market.

IV What are some of the other neglected diseases?

BP Companies also overlook African sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis even though they are far from rare. Three hundred and fifty million people risk contracting leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease that can be either cutaneous or visceral in form. Spread by the tsetse fly, sleeping sickness is endemic in 36 African countries, threatening 60 million people. However, some “neglected diseases” attract more attention than others. Malaria has always raised some interest as travellers to affected countries risk exposure. Another of these better known neglected diseases is tuberculosis. Specialised TB treatment centres still exist in developed countries.

IV How did the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative get started?

BP The project began under the impetus of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). In the early 2000s, the organisation realised that research and development was lacking for a large number of diseases and decided to act. A study shows that only 1% of new drugs developed between

"In emerging countries pharmas could end up focusing on “rich people’s” diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, while a large proportion of the population continues to be overlooked by medical progress."

1975 and 2000 can be used to treat neglected illnesses, which represent 11% of the global burden of disease. This imbalance is not offset by the public sector. And the situation is unlikely to improve as the pipeline of new products is completely empty. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) was set up in 2003 to take action by developing new medicines. France’s Pasteur Institute, the World Health Organization and several research organisations in affected countries have teamed up under the initiative.

IV As an NGO, how does DNDi go about developing a drug?

BP We bring together various public and private partners – companies, public health organisations, research institutions and universities – to focus on one objective. We don’t have a laboratory. The role of DNDi involves pooling resources and coordinating the different actions of our partners throughout the process: research, development, clinical trials and registration. For each project, we work with a pharmaceutical company that commits to producing the treatment on a large scale and selling it at cost price. DNDi has developed six drugs this way. ASAQ, used to treat malaria, is the result of a partnership with the French company Sanofi. The drug is based on a combination of two existing molecules, artesunate and amodiaquine, and was registered in 2007. Since then, 320 million treatments, sold for $1 each, have been distributed on the African market. We hope to develop seven additional drugs by 2018.

IV Your development costs are far below the billion dollars per drug commonly seen in the industry. How do you achieve that?

BP We often either combine existing products that are no longer patent protected or improve drugs on which research has been discontinued. Many companies give us access to their library of molecules. Improving or combining existing formulas costs us between $10 million and $40 million for the entire process, while developing a new drug costs up to $100 million or $150 million. We’re opportunists! We take advantage of discontinued research. Vast scientific knowledge about tropical diseases is out there but has simply not been used to benefit the sick. Our partners contribute by bringing their expertise and investment. We also outsource on a contract basis, but the financial terms are not even comparable to those practised in the industry.

IV Where does DNDi’s financing come from?

BP It’s a balanced combination of public and private funding. We receive money from governments, mainly in Europe, as well as Médecins Sans Frontières. Other contributors include large philanthropic organisations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which donated $60 million to DNDi in November 2014, and the UK-based Wellcome Trust. No single donor provides more than 25% of our budget so that we can maintain diversity in our funding and our independence.

IV Why do pharmas agree to work with DNDi?

BP I’ve noted several factors. In supporting the initiative, pharmaceutical companies improve their image and show they’re concerned about social responsibility. The projects are also extremely well perceived by employees. They meet internal communication objectives. Pharmas also cooperate for commercial reasons, as they gain a foothold in new markets such

“If adequate efforts had been made in the past, a product would already exist to fight the Ebola virus.”

as Latin America, Asia and Africa. By consolidating their position in these regions, they are laying the groundwork to sell other products in the future.

IV Do you also work with Swiss pharmaceutical companies?

BP We have worked with Novartis on several occasions and have minimal relations with Roche.

IV What is your view of the current Ebola outbreak?

BP Huge progress has been made in treating virus diseases, but Ebola has not benefited from it. For the first time, the virus could not be contained to a single geographical region. A short-term response to the crisis was implemented, work on existing drugs resumed, and vaccine potential came out of it. In a few months, researchers identified three candidate vaccines. This clearly shows that if adequate efforts had been made in the past, a product would already exist. It’s not an unattainable goal! However, if the epidemic is brought under control, I still fear that we will fall into the previous trap as the disease mainly continues to affect poor countries.

IV Does this type of event help improve the fate of patients suffering from other neglected diseases?

BP Unfortunately, no. Because there is no risk of sleeping sickness or leishmaniasis spreading in Geneva or New York. But I hope the epidemic will make people realise that research efforts cannot depend exclusively on a system governed by the market. Ebola is a sad illustration of that reality. The market’s inability to meet needs will probably be demonstrated again in the next few years with the growing resistance to antibiotics and the resurgence of certain diseases. It shows the complete short-sightedness regarding the issue.

IV In 2012, the World Health Organization made research and development a priority. What happened to that shift in policy?

BP The initial momentum was followed by half-measures. For example, the WHO’s project to create a global health R&D observatory for developing countries is being put in place, but very slowly. Organisation members will be asked to come up with new proposals in 2016. The WHO reflects what governments want. A long-term solution must therefore come from them, which would involve a change in the regulatory framework, an incentive-based system for developing new products and increased public funding. More public-private partnerships are needed. If no change is made, in emerging countries pharmas could end up focusing on “rich people’s” diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, while a large proportion of the population continues to be overlooked by medical progress.

IV What should be done to wipe out these neglected diseases?

BP Political involvement is absolutely necessary to eliminate the failure of research. But the problem goes beyond that. These diseases are the result of the extreme poverty in which these people live. Reducing poverty would drastically improve the situation.

After graduating from medical school at the University of

Clermont-Ferrand, Bernard Pécoul began his career managing public health projects for refugees. He joined Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in 1983 and carried out several field assignments in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In the early 1990s, he became director of MSF France and later led MSF’s project Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines. Pécoul has been at the helm of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) since it was founded in 2003.