Parents, and some medical professionals, are worried about the effects of vaccines used on their children to immunise them against disease. Specialists offer reassurance.

It began with an innocent question posted on the online medical forum Doctissimo: “Hello, I’m looking for info about vaccinations for babies. I have a four-month old girl who I haven’t had vaccinated yet because I’ve read lots of articles and books about the damaging effects of vaccines (cancers in the long term, neurological problems, etc.).” But the author of the post, Lunaya78, rapidly shifted into attack mode, criticising the power of pharmas, doctors’ lack of transparency and the serious side effects experienced by vaccinated children.

She was quickly joined by another user, who posted a link to a support march for Stacy, a Belgian baby who died of meningococcal meningitis ten days after being vaccinated. On Youtube, the activist Alvin Jackson passionately rants about vaccination requirements for children, comparing them to genocide.

“The huge majority of parents support immunisations, but a small minority, very active in the media and online, is opposed to it,” says Pierre-Alex Crisinel, staff physician with the Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology Unit at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). The opponents mainly cite the dangers of vaccines, which have been denounced as the cause of a string of diseases from autism to multiple sclerosis, allergies, diabetes and epilepsy.

Some parents, especially in the United States and United Kingdom, believe that we should let children develop these childhood diseases to boost their immune system. “There has been a deep change in the perception of risks,” says Claire-Anne Siegrist, Director of the Centre for Vaccinology at the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) and senior physician of General Paediatrics. “People are no longer afraid of the diseases that the vaccines prevent, and so they wonder if they’re of any use at all.”

Some people oppose vaccinations for religious reasons, while others claim the right to choose freely which medicines they give to their children, decrying the immunisation requirements in France and the United States. “Laws are less strict in Switzerland,” says Pierre-Alex Crisinel. “Only the cantons of Geneva and Neuchâtel impose mandatory vaccination against diphtheria. And the new law on epidemics will do away with that require- ment in 2016.”

It’s not just parents who mistrust vaccines. Pierre Verger, an epidemiologist at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm), studied the attitude of 1,712 French general practitioners towards vaccines. “Between 15% and 40% never or only rarely recommend some vaccines,” the scientist says. In fact, one quarter of them feel that we immunise our children too much. “They are the most suspicious of the vaccines that have caused public controversy, such as hepatitis B and papillomavirus.”

Pierre Verger also noted in some practitioners, especially older ones, “a form of defiance” against recommendations from the authorities. For example, the meningococcal C vaccination is considered unnecessary due to the rarity of the disease. Homeopaths, chiropractors and naturopaths are even more reluctant and sometimes hostile towards any practice that contradicts their own doctrine of treating people with plants or back exercises.

This backlash is for the most part unfounded, according to Claire-Anne Siegrist from HUG. “Vaccines with significant harmful side effects never reach the market, and those that furthermore disproved anti-vaccine fears.

Vaccines with significant harmful side effects never reach the market.

“As vaccines are administered on a large scale, people tend to accuse them of triggering all the diseases that this vast group of patients would have developed anyway,” says Bernard Vaudaux, former head of the Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology Unit at CHUV.

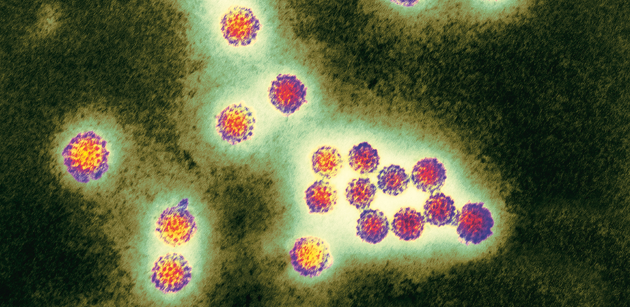

Centre for infections/public health england/science photo library

The frequent changes in the recommended immunisation schedule also lead to confusion. “Some vaccines, such as smallpox and tuberculosis, were dropped because those diseases have disappeared from the indigenous Swiss population,” Bernard Vaudaux says. Other vaccines have been replaced with a new, more effective version, including the vaccine against pneumococcal infections. Certain immunisations are now administered less frequently. For example, tetanus and diphtheria booster shots protect people for longer than expected, so fewer inoculations are necessary between the ages of 25 and 45.

Some caution should

nevertheless be taken with

vaccines. They can be fatal

for people with a deficient

immune system – especially the elderly, newborns

that cannot be immunised

before the age of 1, and HIV patients with poor protection from

antibodies. However, in theory, these

people benefit from the “herd effect”,

which is to say the invisible wall that is

created between them and the disease,

because they live within an immunised

population.

Several European countries, including the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands, suffered measles outbreaks in the early 2000s, resulting from a drop in the vaccinated population following the MMR vaccine scare (see p. 41). The United States recorded nearly 1,000 measles cases between 2013 and 2015. More serious yet, Nigeria and Pakistan have recently faced a resurgence of polio, a disease that had been virtually eradicated, due to the religious authorities’ mistrust of the vaccine. They wrongly accused it of containing pork, which is forbidden in Islam, or of causing sterility as part of a western conspiracy to make Muslim women infertile. ⁄

At the end of the 1990s, an organisation of hepatitis B vaccine victims sparked a controversy in France, saying that they had developed multiple sclerosis. The French Minister of Health at the time, Bernard Kouchner, suspended the use of the vaccine. In the 2000s, the French government and UK pharmaceutical laboratory GlaxoSmithKline had to pay damages to some patients. Several studies have since exonerated the vaccine.

Papillomavirus is a virus that can cause cervical cancer. The vaccine was brought to market in 2006 and is now administered to most teenagers. A group of complainants claims that the vaccine has caused various diseases from multiple sclerosis to hidradenitis suppurativa and lupus. “Some believe that there’s no point vaccinating against a cancer when screening can detect it in its early stages,” says Pierre-Alex Crisinel, staff physician with the Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology Unit at CHUV. The debate is not over.

Controversy broke out in the UK in 1998 following the publication of a paper by the physician Andrew Wakefield in the medical journal “The Lancet”, establishing a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Further investigation revealed that Andrew Wakefield had received money from litigants suing the vaccine manufacturer. “The Lancet” fully retracted the article in 2010.

Newborns often get a combined vaccine that immunises them against several diseases at once. “Some parents fear that the shots overload their immune system and make them more vulnerable to infections,” says David Goldblatt, professor of vaccinology and immunology at University College London. He disagrees: “Every day we deal with millions of bacteria in our intestines, and our immune system does just fine. And thanks to the progress in medicine, the number of antigens contained in vaccines has been reduced in recent years.”

Aluminium is used as an adjuvant in various vaccines. It has been associated with a series of problems. “We noted that aluminium particles can persist at the injection site for an abnormally long period,” says Romain Gherardi, a neuro-pathologist at Paris Est-Creteil University in France. “These particles are responsible for micro-lesions in the deltoid muscle [one of the shoulder muscles] and can migrate to the brain.” He claims to have seen more than 600 patients with this problem. The French National Assembly ordered a report for further study. The report, released in 2013, established no link between the adjuvant and these conditions.