Thanks to medicine and fewer legal restrictions, infertile couples are now more likely to conceive a child. But the process is still complicated and extremely challenging.

On 25 July 1978, all eyes were on Oldham Hospital to the north-east of Manchester (UK). That day, Louise Brown was born. She was the world’s first “test-tube baby”, meaning she was conceived through in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Since then, millions of children have been born throughout the world thanks to this type of assisted reproductive technology (ART), which has gradually become more and more sophisticated. In 2009, the first in vivo assisted fertilisation procedure was performed in Geneva. These two highly publicised events gave new hope to infertile couples—so much so that they believed visiting their doctor was all they had to do to have a child.

According to the Swiss Federal Statistics Office, however, only 37.1% of women treated in Switzerland became pregnant in 2014. In 72% of those cases, the pregnancy resulted in birth. “The success rate of IVF is around 30% on average,” says Nicolas Vulliemoz, director of the Reproductive Medicine Unit (UMR) at Lausanne University Hospital. “This figure depends largely on the age of the mother. It reaches 40% to 50% for women under 30, and falls to between 10% and 15% for women over 40.”

According to the specialist, IVF’s popularity has had a negative impact on research in the field. “Its success limits investment in other techniques and reduces the amount of research funding directed at reproductive medicine,” he says.

Despite IVF’s numerous success stories, it doesn’t solve every case of infertility. Other breakthroughs are currently under development, including the “artificial” production of sperm and eggs (read point 2).

As reproductive science advances, the law is changing as well. In June 2016, Switzerland agreed to change its law regarding assisted reproductive technology, by lessening the constraints and increasing the chances of carrying a pregnancy to term (read glossary). Advocates are also working to improve the psychological support provided to both male and female patients throughout a course of treatment that is both financially and emotionally costly.

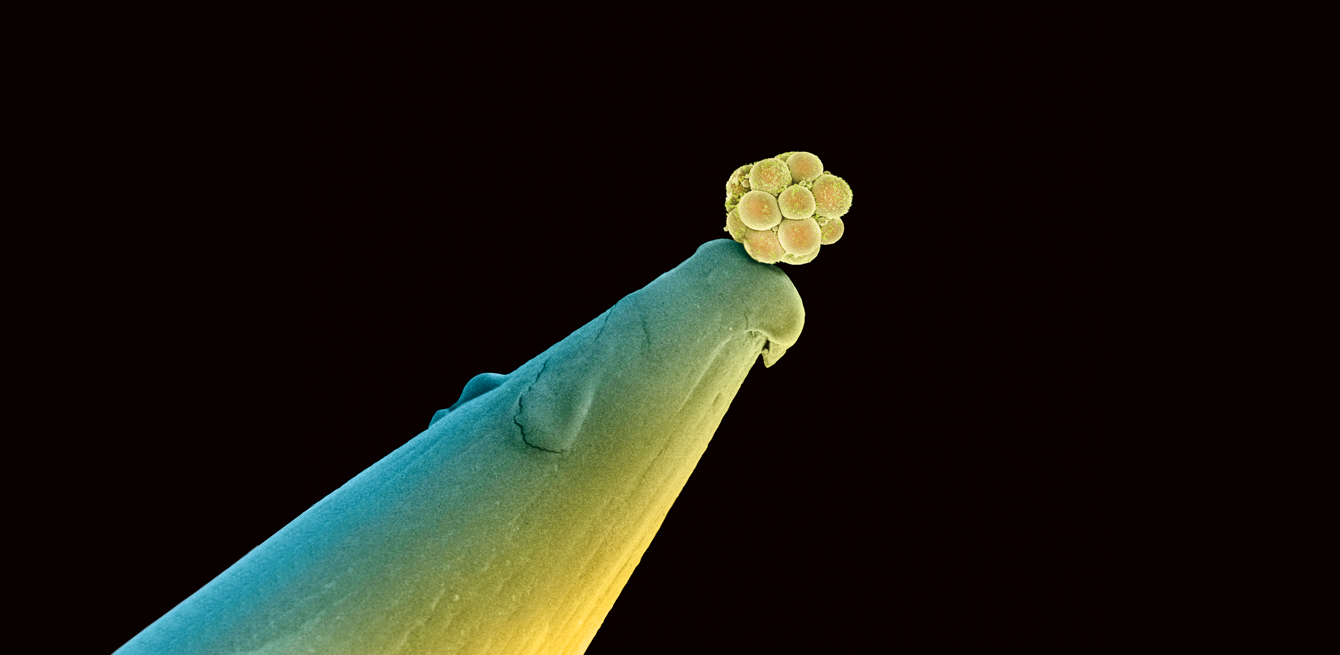

A human embryo made up of 16 cells on the head of a pin as seen by a scanning electron microscope.

1/ A range of causes

Her, him and the couple

A woman’s store of eggs (the sex cells that turn into ovules) is determined at birth. They finish maturing at menopause. So age plays a role in infertility. “Malfunctioning ovaries, an obstruction in the pathways sperm travels to reach the egg and endometriosis are just some of the common reasons why a woman might have trouble conceiving,” says Nicolas Vulliemoz.

“Female infertility is the cause in only 30% of cases,” says Nicolas Vulliemoz

In men, the main causes of infertility are sperm cells that are absent, too few in number or abnormal. “A spermogram can determine whether the shape, mobility and number of the sperm cells are sufficient,” says Laurent Vaucher, a urologist at the Reproductive Medicine Unit (UMR) and the Genolier Clinic (VD). “This test doesn’t give information about the fertility of the sperm, though. It’s just an indicator.”

A couple can have normal results and yet still be considered infertile. “In such cases, there are probably a number of negative factors acting together. Average test results in both partners are often more problematic than a decisive result in just one partner. Right now, we don’t fully understand couple infertility.”

Medical treatments can also damage a person’s ability to reproduce. For example, chemotherapy and radiotherapy—which are toxic to the body’s reproductive cells—can result in temporary or permanent infertility in either sex. In French-speaking Switzerland, the French-speaking Cancer and Fertility Network (RRCF) provides support to these patients. There are techniques that can be used to preserve an individual’s fertility, including gamete (ovules and sperm)cryopreservation prior to treatment.

“For women, the cryopreservation of eggs using vitrification is a major step forward,” says Sébastien Adamski, director of the UMR sperm bank. “Thanks to this technique, pregnancies from frozen eggs are just as successful as pregnancies from fresh eggs. Vitrification prevents the formation of crystals, which damages the egg.” (See our photo report on cryopreservation).

Semen cryopreservation has been available for a long time, but it remains problematic for young boys. “They don’t yet produce mature sperm,” says Sébastien Adamski. “If they have to undergo a toxic treatment, however, it is possible to remove immature testicular tissue and preserve it in the hopes that a procedure for maturing reproductive cells will be developed in the future.”

Some contraceptive methods can also play a role in infertility. A vasectomy, which consists of severing the canals through which sperm travels, is a very reliable contraceptive technique that does not at all change a man’s ability to have an erection or ejaculate. Ejaculation does not just contain reproductive cells. “You should always consider a vasectomy to be irreversible,” warns Laurent Vaucher. In reality, though, it is easy to reconnect these passages to the testicles and allow sperm to pass through once again. However, a vasectomy can affect spermatogenesis, which is no longer 100% guaranteed. The contraceptive pill in women has often been accused of contributing to sterility. But according to Nicolas Vulliemoz, the pill does not decrease a woman’s fertility. A woman simply needs to stop using contraception for a time.

Laurent Vaucher indicates that “an increase in oestrogen (a hormone produced by the ovaries and present in some contraceptive pills) has been clearly observed in the groundwater, where it accumulates because it is present in women’s urine. If the dose is too high, it can cause problems for men. Oestrogen is an endocrine disrupter that affects sperm production.”

In Switzerland, health insurance reimburses three inseminations. If this method is unsuccessful, most couples attempt IVF, which is not covered by insurance.

2/ Technological advances: going beyond IVF, progress within the bounds of the law

Medicine has a range of IVF-based tools that it can use to treat fertility problems. In some cases, issues with sperm production and ovulation can be corrected through medication. For example, women can be given hormones that trigger ovulation. Certain cases may require artificial insemination, in which sperm is delivered to the uterus.

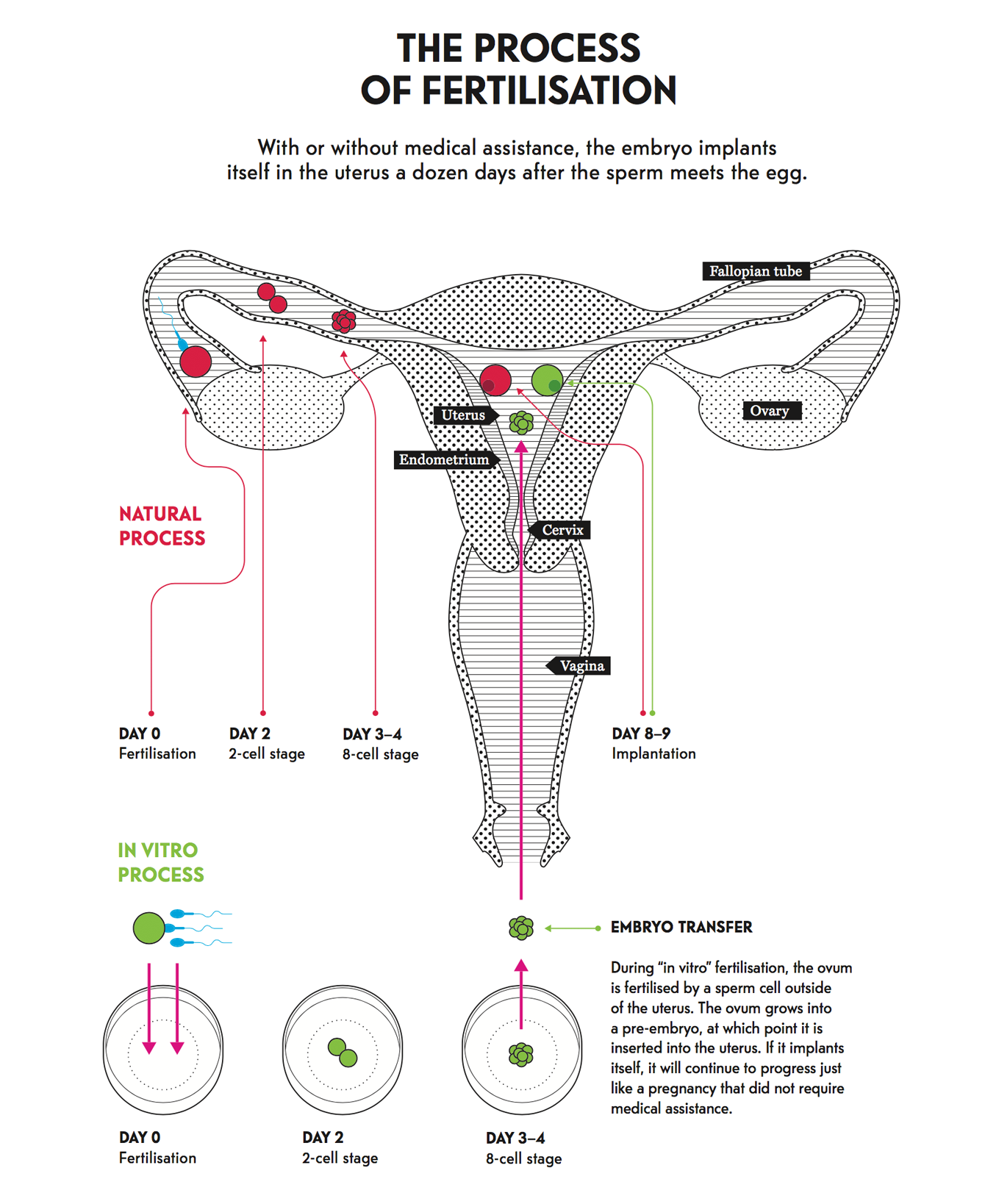

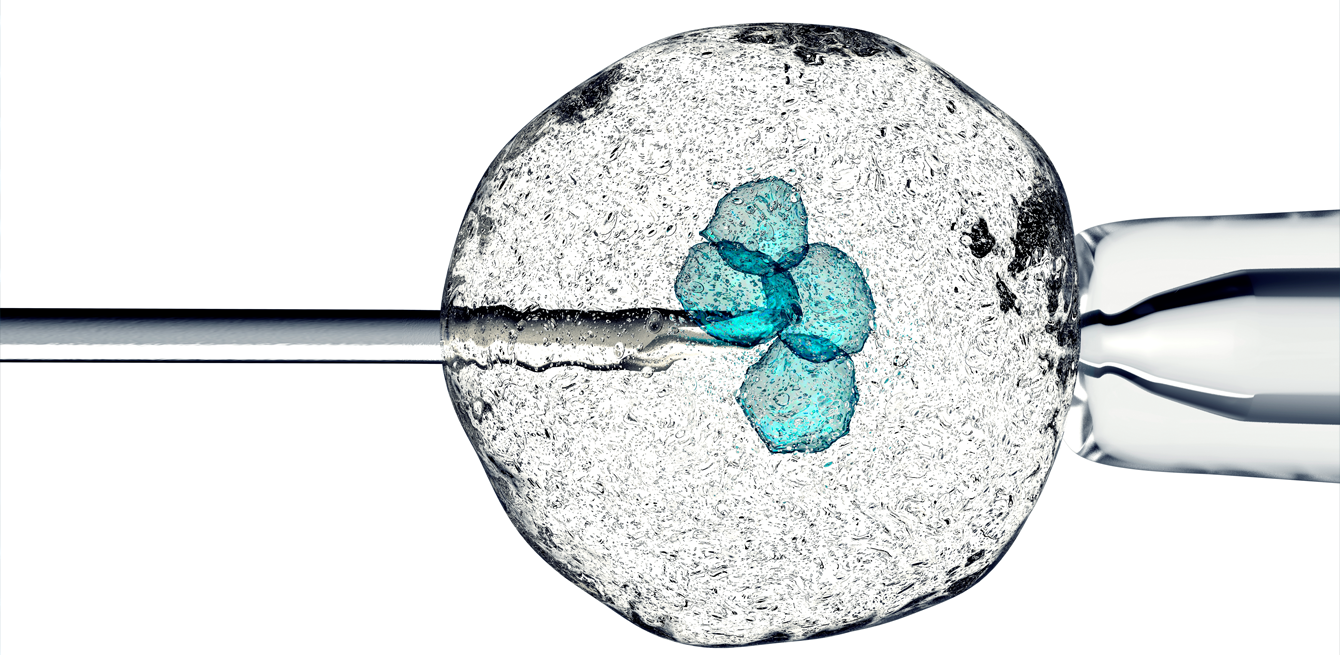

Fertilised eggs are cultured to obtain embryos. In accordance with current practice in Switzerland, three are selected at random to be transferred to the uterus. In the case of male infertility, the eggs are not incubated. Instead, they are injected with a single sperm in a procedure known as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Once it comes into effect, Switzerland’s new law on assisted reproductive technology, which was voted in favour of in 2016, will make it possible to culture 12 embryos, freeze them and perform a pre-implantation diagnosis under strict conditions. “We can protect future babies from certain genetic diseases, but most importantly we can select embryos prior to transfer, which makes the treatments more effective and reduces the rate of multiple pregnancies. This new law will bring assisted reproductive technology in Switzerland up to international standards while also providing the necessary safeguards,” says Nicolas Vulliemoz.

At international level, research on the topic is making significant strides and could eventually offer complementary solutions. One breakthrough that scientists are working towards involves the production of sperm-producing cells in vitro.

“Several international research groups have announced they’ve reproduced mice sperm that has resulted in the birth of baby mice,” says Laurent Vaucher.

Another field of research seeks to generate sperm from skin or bone marrow stem cells in animals, though it is not as far along. “Some of these techniques could yield results in just a few years. Nevertheless, the maturing process is more complex in humans than in mice,” says Sébastien Adamski.

The production of artificial gametes could potentially no longer require a donation. “There aren’t enough sperm donors,” says Sébastien Adamski, “whereas egg donation is flat out banned in Switzerland.” As a result, many Swiss couples must travel abroad to receive this type of donation (see testimonial herafter).

P. and B.*, a couple from Geneva, travelled to Spain to receive an egg donation. They share their experience, which resulted in the birth of their son.

The eight-month-old baby tries to turn over in his crib beneath the watchful eyes of his parents. The happy scene contrasts with the decade of challenges and setbacks that led to this moment.

“It felt like an eternity,” says the young mother. “After three years of trying to become pregnant, my partner and I consulted a reproduction medicine specialist in Switzerland. Our tests were normal except for a low sperm count. After three artificial-insemination procedures,

we still didn’t have any medical explanations. It was when we switched to IVF that the technician discovered the problems with my eggs. The doctor remained optimistic, so we tried IVF another time, without success. The lack of explanation led us to consult another doctor.”

Their new doctor suggested alternatives. “He discovered that I had endometriosis, and operated on me. We were hopeful. But when the doctor saw the state of my eggs during the third IVF treatment, there was no question—we either had to adopt or use a donated egg. After struggling for seven years, we wanted to give ourselves another chance and opted for Spain.” The most disorienting part of the experience was encountering Spain’s business-oriented approach to medicine. “To get the treatment, we waited in line like at the butcher shop.” Organising this type of trip is complicated. “You have to take off from work, weather the side effects of hormone treatments and go about your day-to-day work without being able to talk about it. It was all the more difficult because the first two transfers didn’t take. But finally, the third one worked!”

After a significant amount of work on herself, the mother had a successful donation and carried her pregnancy to term. The couple spent over 60,000 Swiss francs for all the treatments. But it wasn’t the lack of insurance coverage the couple found shocking: “I don’t understand why sperm donation is allowed in Switzerland but not egg donation.”

3/ Listening to hardship

Necessary psychological support

In addition to medical treatments, specialists strongly recommend that couples receive psychological care as well. Moreover, Switzerland’s law on assisted reproductive technology makes it a requirement before, during and after treatment. “The road isn’t a simple one,” warns Danièle Besse, sexual health counsellor at the Reproductive Medicine Unit. “When a doctor looks for the causes of infertility, one partner might feel responsible or even guilty, which can create problems within the relationship.” In addition, once the diagnosis has been made, a more or less complex treatment is recommended. “Couples don’t always expect how the treatments will affect their bodies and sexuality. They underestimate the probability of failure. Assisted reproductive technology involves waiting, hoping and experiencing setbacks. It’s a roller coaster that is hard on the psyche,” she says.

“Often, couples feel that doctors aren’t listening or even supportive,” says Estelle Métrot, a pre-conception support specialist based in Geneva and Paris and the author of the book 1001 fécondités. “It’s imperative to pair medical innovation with opportunities for counselling.”

Suffering can affect both people in the couple. “Some people might not feel like women if they can’t be mothers,” says Danièle Besse. “Men are quicker to associate fertility with virility and can therefore have a hard time dealing with infertility.” Estelle Métrot points out that reproductive medicine takes a greater toll on the woman’s body. “Women can be put through many tests during the exploratory and treatment phases. It’s the woman who undergoes stimulation treatments, who is poked and prodded and whose body is exposed to others on a regular basis.”

Geneva-based Pascale de Senarclens decided to end her treatment because of inadequate psychological support, among other reasons (read testimonial). “The technology doesn’t mitigate the emotional impact.” (read Pascale Senarclens interview). /

In medicine, infertility and sterility are not the same. Sterility refers to someone who is permanently unable to reproduce. Infertility is the temporary absence of conception.

FALSE

In Switzerland, children of sperm donors can learn the donor’s identity when they turn 18. Before conception, a donor is selected depending on ethnicity and hair and eye colour. Each country has its own legislation on the matter. Some foreign sperm banks provide donors’ photos or even Facebook pages depending on the price paid by the recipient.

FALSE

It’s fecundity that

is decreasing, meaning the fulfilment of a person’s desire for a child. In addition, even though it’s widely known that hormone and pesticide pollution is causing a drop in sperm count in men, “their rates remain far above a level that would constitute infertility,” says Laurent Vaucher. A study published in the review PLOS in 2012 and validated by the World Health Organization confirmed this conclusion.

The research, which used data collected between 1990 and 2010, indicates that global fertility has not dropped except in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

TRUE

In 2015, the first child whose mother had received a uterine transplant was born in Sweden. The study, which was published in the journal The Lancet, reports that the mother received a uterine transplant from her 61-year-old menopausal friend. One year after the operation, the mother underwent IVF using her own eggs and her husband’s sperm. “This technique is extraordinarily complex and involves multiple risks. We weren’t sure the procedure was even feasible, which makes this breakthrough very significant,” says Nicolas Vulliemoz.

FALSE

In Switzerland, donation is limited to eight children per donor to limit consanguinity.

The number of births in 2016. 43,759 boys and 41,889 girls were born.

A mother’s average age at the birth

of the first child, in 2016.

In 2014, the number of couples who used

“in vitro” fertilisation. This technique has resulted in the birth of 1,955 children.

The number of births by Caesarian section in 2015, or over one in three births.

This is a gynaecological disorder whose name derives from the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus. In some women, tissue that resembles the endometrium grows outside the uterine cavity, resulting in extreme pain, bleeding, adherence and ovarian cysts. This disorder increases the risk of infertility.

With this type of assisted reproductive technology, an egg is fertilised with sperm outside the woman’s body in a laboratory test tube, i.e. in vitro. The resulting embryo is then implanted in the mother’s uterus.

This kind of assisted reproductive technology selects an egg and sperm before implanting them directly in the uterus. Fertilisation occurs within the woman’s body—or in vivo—rather than in a laboratory.

A female sex cell produced by the ovaries. Oocytes become ova after they mature.

This term describes the process of sperm production. It starts at puberty and occurs within the testicles.

The Swiss law on assisted reproductive technology regulates the methods, such as IVF, that can be used to artificially induce pregnancy. In Switzerland, this law was first adopted in 1998 and later modified in 2016. It allows up to 12 eggs to be harvested and authorises a pre implantation diagnosis on the embryos to detect potential abnormalities prior to transferring them to the uterus. The goal of the pre implantation diagnosis is to only transfer healthy embryos, thereby optimising the likelihood of pregnancy for struggling couples.

Smart technology can also be used to help reproduction. A Swiss-designed connected bracelet is a notable example of this type of technology. The accessory, created by the Zurich-based start-up Ava, used physiological measurements that correlate with changes in hormone levels—such as pulse, sleep and temperature—to predict ovulation. The bracelet was approved by the FDA and will soon be marketed in Switzerland. Ava raised $9.7 million in November 2016. The money will be primarily invested in research and clinical studies. There have reportedly been eight babies born to mothers using Ava in 2017 already.

Even though it’s authorised in 20 other European countries, human egg donation is still banned in Switzerland. As a result, hundreds of Swiss couples travel abroad every year to receive treatment (read testimonial on the left). Several members of Parliament have already questioned why Switzerland continues to ban egg donation even though the country’s first law on assisted reproductive technologies (LPMA) legalised sperm donation in 2001. In 2014, the Swiss National Councillor Jacques Neirynck (PCD/VD) submitted a parliamentary proposal to authorise the practice. The initiative was eventually abandoned in 2016. “There was no opposition to the substance of the law,” said Isabelle Chevalley (PVL/VD). “However, several laws would have had to be modified to lift the ban on egg donation. At the time, some members of Parliament thought it was too complicated. In my opinion, that is not a valid reason.” Last March, the National Councillor co-signed a motion to ask the Swiss Federal Council to legalise egg donation. If the Council agrees, the decision would enter into effect in two years at the earliest—a timetable Isabelle Chevalley judges to be “very optimistic”.