Every human being has approximately two kilos of bacteria, yeast, fungi and other viruses in their body. Taming these microorganisms could turn them into valuable allies.

Each individual permanently bathes in a vast soup of microorganisms.” This is the image that Thierry Calandra, chief of the Infectious Diseases Service at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) uses to explain that a considerable proportion of the human body consists of microbes. Even so, science knows very little about these invisible visitors, estimated at 100 trillion in each person (100’000 billions), i.e. ten times more numerous than human cells, with a total weight of about 2 kilos. To remedy this, a vast project called the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) was started in 2007.

Launched by the US National Institutes of Health, this long-term $195 million programme aims to identify the microbes that live on humans and decipher their genome in order to understand how they affect the human being. It’s a meticulous task that is leading to promising prospects in terms of new treatments.

This gigantic quantity of microbes is nothing to panic about: far from attacking the body, microbes help protect it. “Most of these microorganisms help the body maintain its functional equilibrium,” says Thierry Calandra. “Even better, they are continuously building up the immune system to enable our body to deal with them.” To the point where the cohabitation between a human host and the microorganisms that colonise it resembles a strategic partnership. Some microbes serve as a first line of defence, attacking pathogens or preventing them from developing. But they are fragile fortifications: travelling, an antibiotic treatment, or a change in diet may disrupt this delicate balance and increase the risk ofinfection or inflammation.

Most of these microorganisms help the body maintain its functional equilibrium.

Can we intentionally develop this balance, for preventive or curative purposes? “It’s already happening,” says Thierry Calandra. “It’s been known for a long time that the transplantation of faeces from one healthy individual to a patient with diarrhoea helps the latter’s recovery.”

By refining their knowledge of how the microbial world and our body influence one another, microbiologists and doctors can hope to reduce certain risks in the long term, and even treat various diseases by “adjusting” the microbiota. Studies in progress suggest that there may be huge possibilities in a variety of fields: psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, obesity, ulcerous colitis, allergies, acne, etc. There is vast potential, but “the complexity of this equation with many unknowns prevents us from knowing when we will be able to move on to concrete clinical applications,” stresses Thierry Calandra.

And although researchers are working tirelessly, the road is still very long: the HMP is dedicating over 2,600 projects to the sequencing of the microbial genome. Only 15 of them are currently dedicated to the search for hypothetical correlations between the microbiome and human health. The slow pace is explained by the complexity of protocols and an out-of-the-ordinary indexing effort: a human being has 20,000-25,000 genes. In six years, the 80 laboratories involved in the HMP have already identified 8 million microbial genes…

The microbiota of a human being is continuously changing in terms of age, environment and diet. This does not make it easy to conduct research.

Beyond the therapeutic prospects, the HMP studies are helping to slowly refine knowledge of microorganisms, demolishing certain preconceptions. “Most microbes are either useful or harmless,” says Amelio Telenti, professor at the CHUV Microbiology Institute. Microbes that proliferate in our intestines carry out essential digestive functions: bacteria in the intestines break down certain carbohydrates and encourage absorption by the body of the very essential vitamin K.

This complex combination of hundreds of different species turns each human being into a macrocosm populated by a particular microcosm. “Eventually, we could probably identify an individual by analysing the entirety of their flora,” says Amelio Telenti. At least in theory: “The microbiota of a human being is continuously changing in terms of age, environment and diet. This does not make it easy to conduct research.” So it will probably be some time yet before policemen will be taking samples of intestinal flora rather than fingerprints.

Every human being has approximately two kilos of bacteria, yeast, fungi and other viruses in their body.

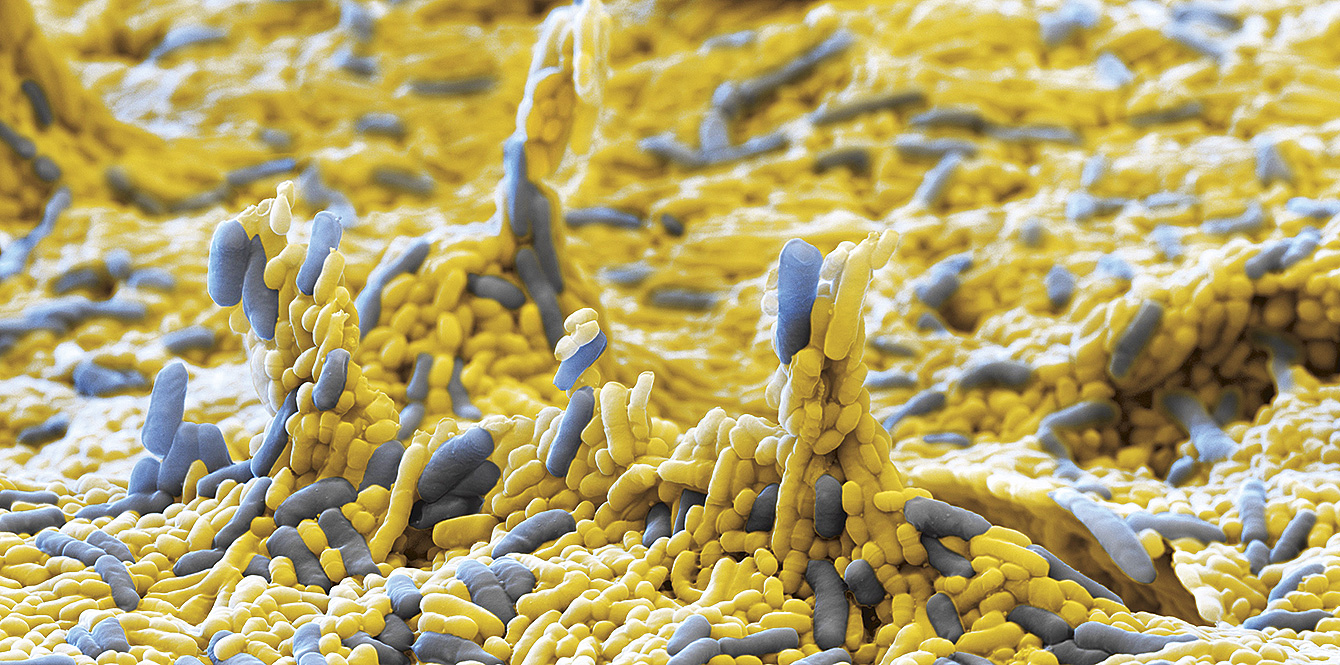

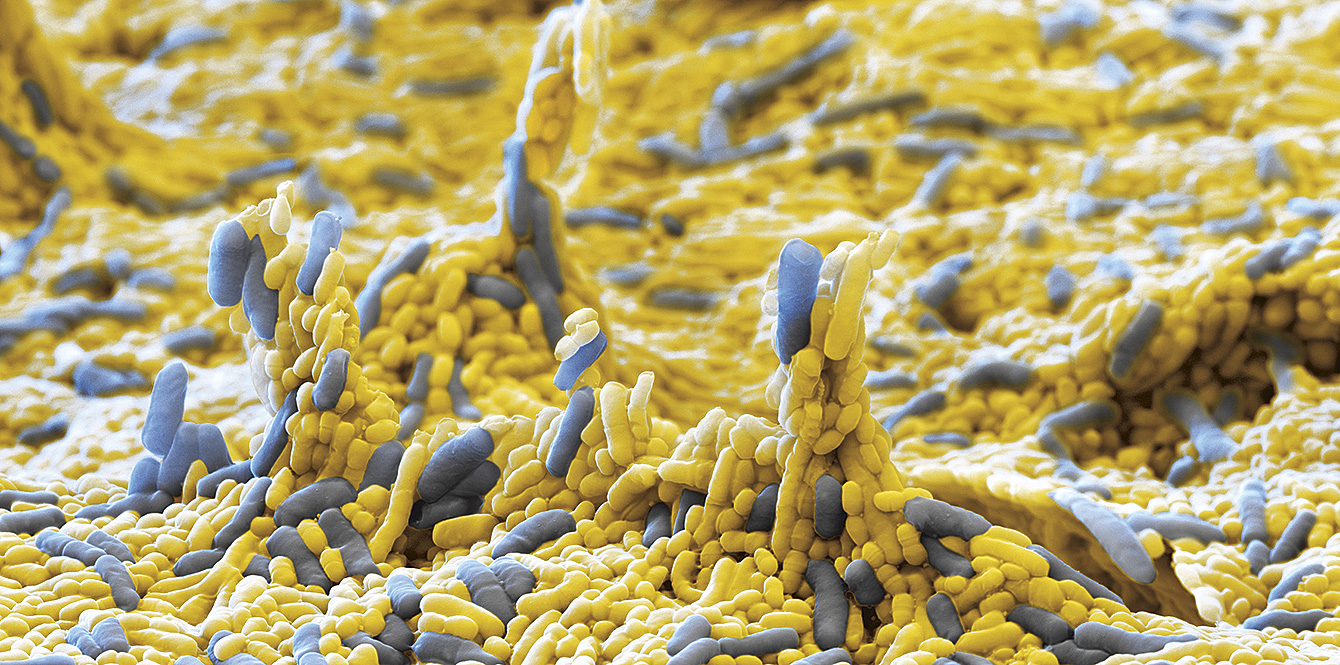

This image obtained by an electronic scanning microscope shows a “Lactobacillus casei”. This bacterium produces bacteriocins, which are proteins that have antibiotic properties. They can thus prevent certain infections in humans.